Regenerated forest Antioquia

From Cattle Ranch to Regenerated Forest: What 23,000 Trees Taught Me About Busines

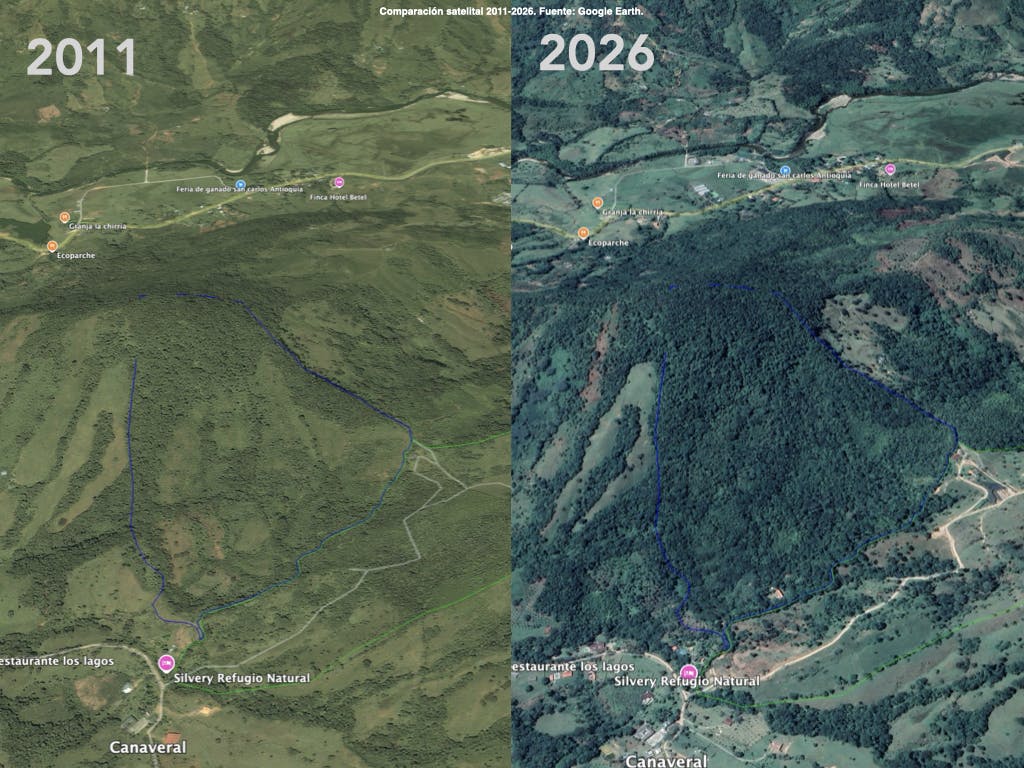

Twenty years ago, this place was an abandoned cattle ranch. Degraded pastures. Weak water springs. Little life. Today it is a forest with 23,000 trees, more than 110 bird species, and a business model that learned to think in decades instead of quarters.

When my sister and I bought this land in San Carlos, Antioquia, the region was still carrying the weight of armed conflict.

A friend invited us to invest in something almost no one understood at the time: a neglected hillside in a place where few were willing to bet on the future. We didn’t fully understand what we were doing either.

We only knew one thing: we wanted to leave the land better than we found it.

The Decision Few Applauded

Buying land in a post-conflict area was not obvious. Planting trees instead of continuing cattle ranching, the economically sensible choice, made even less sense to many.

Still, we started. We planted 23,000 trees. Mostly native species: cedar, ceiba, balso, abarco, guayacán, walnut, and bamboo. We also planted melina, an introduced species.

We generated more than 20 local jobs. We got blisters on our hands. We built friendships.

No one applauded at the beginning. The results were not immediate. Over time we understood something that would later shape Silvery: forests do not operate in quarterly cycles. They operate in the long term.

What the Forest Gave Back

The transformation didn’t arrive with headlines. It arrived with sounds. Each year, more birds could be heard. A family of silvery brown tamarins (Saguinus leucopus) multiplied. Neighbors began speaking about a “tiger” living in the forest. Our camera traps confirmed it: an ocelot (Leopardus pardalis).

The water changed. Mountain springs increased their flow and became consistent. Clear, steady water is a quiet signal of ecological recovery.

In 2024, together with the Geolimna research group from Universidad de Antioquia, we documented more than 110 bird species on the property. An environmental engineering student wrote her thesis here. The forest stopped being a personal project. It became a living laboratory. None of that was part of the original plan. The forest exceeded our expectations.

The Lesson No Business School Teaches

At some point, I understood something that permanently changed how I think about business: Biodiversity is not an ecological accessory. It is infrastructure. And infrastructure generates return.

The water that emerges between our trees is not storytelling. It is the asset that makes our guest experience possible. The 110 bird species are not marketing data. They are the reason someone drives three hours from Medellín to get here. Living soil is not romanticism. It is an asset that sustains the local economy of the Cañaveral community.

Regeneration was not a cost. It was the investment with the greatest long-term return we have made.

If Silvery exists today as a business, it is because the forest existed first.

Why This Matters Beyond Silvery

The Colombian Andes sustain much of the water that supplies cities, industry, and agriculture. The pressure here is not only ecological, it is systemic.

Energy, water, population, and biodiversity converge in this region. If regeneration does not happen here, balance is impossible.

The extractive model has reached its limits. The next cycle of value creation lies in learning how to protect the systems that sustain us.

Silvery is still an ongoing experiment. We do not have all the answers. But we have twenty years of evidence that it is possible to build a profitable business that simultaneously regenerates the territory where it operates.

That is not utopia. It is strategy.

After Walking This Forest, the Conversation Changes

It is no longer about sustainability as a cost. It is about regeneration as a business strategy.

Come and see it for yourself.

Then we can talk about business.

___

By Edgar A. Martinez Londono

Sanitary Engineer, MSc, PhD in Environmental Engineering

Founding Partner of Silvery Nature Haven